like this

Regan Golden, “Painting the Present”

October 12, 2016

Amanda Hamilton's new series of small works grapple with the transcendence and despair of our present moment, with thick swaths of gold-flecked gray paint offset by live plants, to remind us we, too, are rooted here and now.

"Even if one no longer speaks of painting as a window opened onto the world, the modernist picture is still conceived as a vertical section that presupposes the viewer’s having forgotten that his or her feet are in the dirt."

Yves Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide

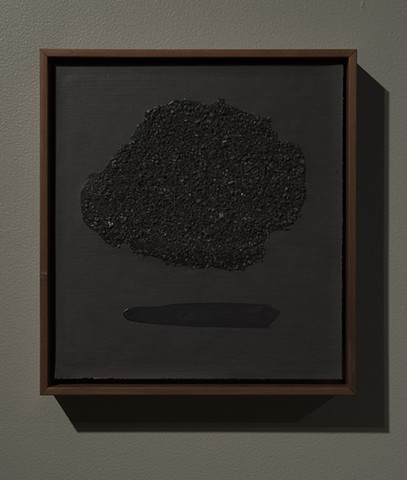

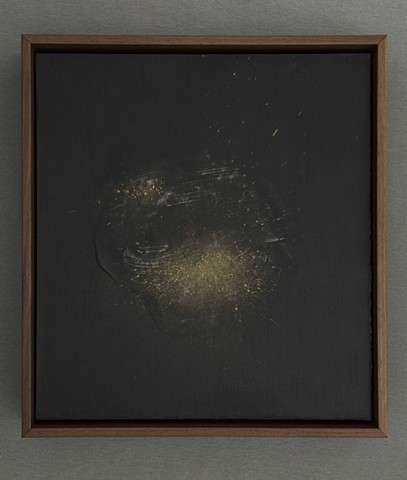

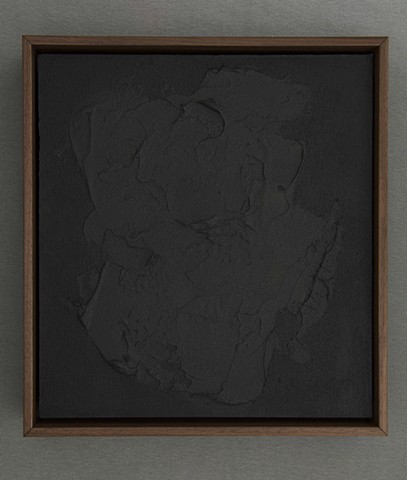

Amanda Hamilton‘s 11 small, new paintings in her exhibition like this at Bethel University grapple with transcendence, despair, and the legacy of Abstract Expressionism through thickly applied layers of gray and gritty paint flecked with gold. Yet, Hamilton’s gestural paintings and their philosophical underpinnings might appear inaccessible or outmoded, were it not for the comfortable sofas and vibrant potted plants alongside them.

Hamilton carefully structures the environment in which these paintings are viewed as a counterbalance to their gravity, in both senses of the word. Dark swaths of paint hang heavy on the page. The paintings started as a way to make time to listen and respond to all the stories of violence and tumult in the daily news. The paintings, some 80 total, are a way for Hamilton to carve out time to be present to these tragedies and to inscribe her emotional reactions on this painted surface. This is palpable in the paintings, whose shimmering surfaces transcend the ordinary only for a moment, until the same muddy marks remind us that our “feet are in the dirt.”

The paintings are a way for Hamilton to carve out time to be present to these tragedies and to inscribe her emotional reactions on this painted surface. This is palpable in the paintings, whose shimmering surfaces transcend the ordinary only for a moment, until the same muddy marks remind us that our “feet are in the dirt.”

Hamilton creates a meditative space in the gallery, inviting people to search for hope in a difficult situation. This is manifest not only in the gold and silver “linings” of the paintings, but also in the impossibly lush green plants growing in an environment with limited light and fresh air. The gallery walls are nearly the same hue as the paintings — a deep gray-green — and at the center of the room an array of plants spring from gray cubed planters. The plants cast shadows across the gallery floor that resonate with the organic marks in the paintings. While the paintings appear like still images of dissolution, the plants are just the opposite, as they grow and thrive and decay in the gallery.

Around the perimeter of the gallery three small sofas, also dark gray, are positioned for people to sit on, but they are not parked directly in front of the paintings. Hamilton built the sofas, the planters, and the frames for the paintings in similar colors and proportions, unifying the exhibition as a whole. Asking the audience to take a seat beside these mucky glistening surfaces, Hamilton upends the idea that paintings can only be transcendent when they disconnect themselves from decorative objects and everyday life.

On their own, the paintings might get too close to rehashing Clement Greenberg’s 1961 essay, “Modernist Painting,” where he argues that Abstract Expressionist paintings can transport the viewer through a form of reified vision into a sublime “third realm.” The exhibition space as a whole keeps these paintings tethered to the earth, materially and conceptually. What evolves is a contemporary definition of painting that is expressive and alluring, contemplative and grounded.